|

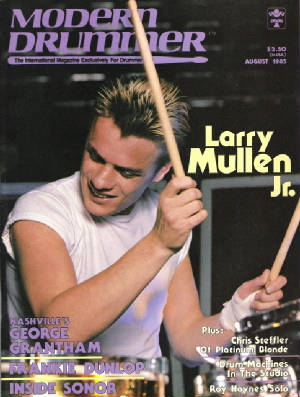

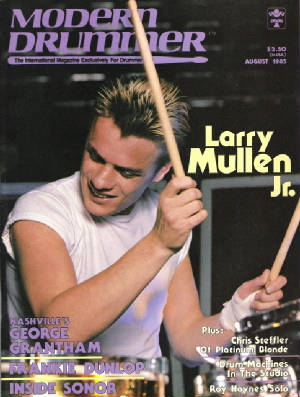

MODERN DRUMMER - August 1985

Note: This interview also in: PROPAGANDA issue 1 - 1986

Voted Number One in the Up & Coming category of MD's 1985 Readers Poll, Larry Mullen Jr. is a different drummer.

A universal blend of past and future, East and West, primitive and classical, his sound is huge and heroic. Even

before he began drumming with U2 at the age of 16, he was, in his own words, "unteachable". Logic and reason do not

define his approach to drumming; spirit and instinct do. He treats each song as an experiment. U2 bassman Adam

Clayton refers to Larry's "dignity" as a drummer and adds, "He won't play anything that isn't natural to him." Assigned

with a long shopping list of percussive paraphernalia to set up for experimentation in Larry's new home, drum roadie Tom Mullally

describes Larry as "not demanding." But Mullally continues, "If he gets an idea, we work bloody hard to make sure it

happens. He'll turn everything upside down." Rebelling against the clutter in so much music, Larry allows the

freshness and freedom of the open space to be important, and in the drummer's dangerous world of time and space, he knows

when to hit and when not to hit. At 23, he's a young master. Unlike most musicians his age, he seems to have already

lost his taste for "stardom", if he ever had it. This interview explores the thoughts of a drummer who holds his ground.

Whatever it took for Larry Mullen, Jr., to become himself, he made it. And he is truly one of the most gifted

and innovative drummers in the world today .

LM: Let me say first of all that I don't do interviews, ever. I did them when the band first started, and

then I stopped because I didn't enjoy them. I've seen issues of Modern Drummer. I like what the magazine

does, so I decided to do this. But I'm not a talker; I hope you can make sense of what I say. I saw a piece on

Russ Kunkel about how musical he is and all that. I don't deserve that kind of praise in a technical sense; I don't

consider myself great by any means. I wouldn't want the magazine to make me something I'm not. But what I do feel

is that, if I'm going to do an interview, I want people to know that you don't have to be a technical drummer. You can

follow your own rules and be in a successful band. LM: Let me say first of all that I don't do interviews, ever. I did them when the band first started, and

then I stopped because I didn't enjoy them. I've seen issues of Modern Drummer. I like what the magazine

does, so I decided to do this. But I'm not a talker; I hope you can make sense of what I say. I saw a piece on

Russ Kunkel about how musical he is and all that. I don't deserve that kind of praise in a technical sense; I don't

consider myself great by any means. I wouldn't want the magazine to make me something I'm not. But what I do feel

is that, if I'm going to do an interview, I want people to know that you don't have to be a technical drummer. You can

follow your own rules and be in a successful band.

CF: I think you're underestimating yourself. CF: I think you're underestimating yourself.

LM: Maybe. There's no harm in that. It means that I'll continue to grow, hopefully. LM: Maybe. There's no harm in that. It means that I'll continue to grow, hopefully.

CF: Your music projects a global consciousness, but your roots are firmly in Ireland. What was it like to

grow up there? CF: Your music projects a global consciousness, but your roots are firmly in Ireland. What was it like to

grow up there?

LM: There's no comparison with America or even Europe. It's a very isolated country – a totally different

world. Things like abortion, contraception, and pornography don't exist. You have to fight – very hard –

if you want to do anything different. To be in a band is really, really difficult. There's nowhere to play.

But it's an interesting and beautiful place, too. I live there now; I wouldn't live anywhere else. It doesn't

have the pressures of rock 'n' roll. Somebody says, "There's the drummer from U2." Another person answers, "So

what?" In America or anywhere else, you come out of the hotel, and people want to take bits out of you. In Ireland,

people have respect, and they leave you alone. LM: There's no comparison with America or even Europe. It's a very isolated country – a totally different

world. Things like abortion, contraception, and pornography don't exist. You have to fight – very hard –

if you want to do anything different. To be in a band is really, really difficult. There's nowhere to play.

But it's an interesting and beautiful place, too. I live there now; I wouldn't live anywhere else. It doesn't

have the pressures of rock 'n' roll. Somebody says, "There's the drummer from U2." Another person answers, "So

what?" In America or anywhere else, you come out of the hotel, and people want to take bits out of you. In Ireland,

people have respect, and they leave you alone.

CF: Did you spend much time by the ocean? Sounds of the ocean come across in some of your bass drum and cymbal

work. CF: Did you spend much time by the ocean? Sounds of the ocean come across in some of your bass drum and cymbal

work.

LM: Yes, I grew up in Dublin. You've always got the sea. From where I lived, it's about 500 yards down

the road. Dublin has about a million people, but if you go just a mile outside the city, it's very peaceful, with green

trees, and all the things you'd imagine are in Ireland. LM: Yes, I grew up in Dublin. You've always got the sea. From where I lived, it's about 500 yards down

the road. Dublin has about a million people, but if you go just a mile outside the city, it's very peaceful, with green

trees, and all the things you'd imagine are in Ireland.

CF: Were you into native Irish music? CF: Were you into native Irish music?

LM: Well, obviously, I listened to it. When I was growing up, there wasn't one rock 'n' roll station in Dublin.

There was a station that played an occasional Beatles' song, but if you wanted to hear rock 'n' roll. You had

to tune into a pirate radio station or a British radio station like Radio Luxembourg. I'd have my pocket radio under

my bed, trying to tune in Radio Luxembourg so I could hear the charts. It wasn't until around the last five years that

new bands would come to Ireland; before that, very few came. The Stones came about two years ago, which was the first

time since '76 or '77. Now rock 'n' roll is big in Ireland. It's just that very few can survive playing it or doing

anything original. LM: Well, obviously, I listened to it. When I was growing up, there wasn't one rock 'n' roll station in Dublin.

There was a station that played an occasional Beatles' song, but if you wanted to hear rock 'n' roll. You had

to tune into a pirate radio station or a British radio station like Radio Luxembourg. I'd have my pocket radio under

my bed, trying to tune in Radio Luxembourg so I could hear the charts. It wasn't until around the last five years that

new bands would come to Ireland; before that, very few came. The Stones came about two years ago, which was the first

time since '76 or '77. Now rock 'n' roll is big in Ireland. It's just that very few can survive playing it or doing

anything original.

CF: CF: How did you become a drummer?

LM: I started at about nine; I used to play piano. The teacher was really a nice lady, but one day she said,

"Larry, you're not going to make it." (laughs) She suggested that I try something else. I was delighted, because

I had wanted to say the same thing to her a year before that. LM: I started at about nine; I used to play piano. The teacher was really a nice lady, but one day she said,

"Larry, you're not going to make it." (laughs) She suggested that I try something else. I was delighted, because

I had wanted to say the same thing to her a year before that.

CF: But your parents were making you take lessons? CF: But your parents were making you take lessons?

LM: Well, they thought it would be good for me to be exposed to music, and since I liked music, I went along with

it. But I wasn't good at piano; I didn't practice much. So, as I walked away from my last piano lesson at the

College of Music, I heard somebody playing drums. I turned around to my old lady and said, "You hear that? I want to

do that." She said, "Okay. If you want to do that, you'll pay for it yourself!" So at nine years

of age, I saved up a bit of money and I got nine pounds for my first term of drum instruction. I wasn't very good at

learning or technique; I didn't practice much, because I was far more interested in doing my own thing. I wanted to

play along with records like Bowie and the Stones. I didn't want to go through the rudiments – paradiddles and

all that stuff, you know. I carried on with this teacher for about two years, and I just got bored. This is terrible,

but he passed away, and [pauses] I mean, I was only a kid: I said, "Wow, Divine Intervention! I don't have to do this

anymore!" (laughs) So I joined a military-style band: fife and drum – all that sort of stuff. LM: Well, they thought it would be good for me to be exposed to music, and since I liked music, I went along with

it. But I wasn't good at piano; I didn't practice much. So, as I walked away from my last piano lesson at the

College of Music, I heard somebody playing drums. I turned around to my old lady and said, "You hear that? I want to

do that." She said, "Okay. If you want to do that, you'll pay for it yourself!" So at nine years

of age, I saved up a bit of money and I got nine pounds for my first term of drum instruction. I wasn't very good at

learning or technique; I didn't practice much, because I was far more interested in doing my own thing. I wanted to

play along with records like Bowie and the Stones. I didn't want to go through the rudiments – paradiddles and

all that stuff, you know. I carried on with this teacher for about two years, and I just got bored. This is terrible,

but he passed away, and [pauses] I mean, I was only a kid: I said, "Wow, Divine Intervention! I don't have to do this

anymore!" (laughs) So I joined a military-style band: fife and drum – all that sort of stuff.

CF: Why did you want to join that? It seems like more regimentation. CF: Why did you want to join that? It seems like more regimentation.

LM: Because it was more of a goof, because there were girls in this band, in the Color Guard. LM: Because it was more of a goof, because there were girls in this band, in the Color Guard.

CF: I've seen some of those bands in competition. They can be quite sophisticated in their musicianship. CF: I've seen some of those bands in competition. They can be quite sophisticated in their musicianship.

LM: Not this one. It was more "Let's have a good time and march in the St. Patrick's Day parade in Dublin."

They would try to make us read music as well, and I could read, but this other guy and I said, "This sounds too drab

off the sheet." So we just threw the sheet music away and invented our own things. I was in that band for two

years, including the early days of U2. LM: Not this one. It was more "Let's have a good time and march in the St. Patrick's Day parade in Dublin."

They would try to make us read music as well, and I could read, but this other guy and I said, "This sounds too drab

off the sheet." So we just threw the sheet music away and invented our own things. I was in that band for two

years, including the early days of U2.

CF: I've read that you got kicked out of a military band. CF: I've read that you got kicked out of a military band.

LM: That was another band, the Artane Boys' Band. The band I was just telling you about was a bit more

loose – a little freer. The Artane band was too rigid for me. I was in for three days, and they told me

get my hair cut. And at the time, it was my pride and joy – you know, shoulder-length golden locks. So I

got it cut a few inches, and they told me to cut it more. So I told them to stick it, and I left! (laughs) I'd

forgotten about that. LM: That was another band, the Artane Boys' Band. The band I was just telling you about was a bit more

loose – a little freer. The Artane band was too rigid for me. I was in for three days, and they told me

get my hair cut. And at the time, it was my pride and joy – you know, shoulder-length golden locks. So I

got it cut a few inches, and they told me to cut it more. So I told them to stick it, and I left! (laughs) I'd

forgotten about that.

I had a stage, too, when a guy tried to teach me jazz drumming, but again, the same problem. This teacher was really

into Steven Gadd: Steve Gadd was his idol. I think Steve Gadd is a great drummer, but this teacher would play Gadd's

records and tell me to play like that. I was rehearsing with U2 as well then, so I gave it up. I just couldn't

sit there and imitate someone else.

CF: The story has it that you founded U2. CF: The story has it that you founded U2.

LM: Yes, and I was in charge for about three days! (laughs) We were all in the same school, and the prospect

of leaving school and getting a job wasn't there. There were no jobs to get. It was like we were all going nowhere,

so we decided to go nowhere together and form a band. Our school was an experimental, interdenominational school, quite

liberal and open. We had to do our work, and if we were interested in sports or music, for instance, we were actually

given time. They gave us a room to practice in. There were very few schools in Ireland like that. Most were

Christian Brothers schools where you studied, did your work, and that was it. LM: Yes, and I was in charge for about three days! (laughs) We were all in the same school, and the prospect

of leaving school and getting a job wasn't there. There were no jobs to get. It was like we were all going nowhere,

so we decided to go nowhere together and form a band. Our school was an experimental, interdenominational school, quite

liberal and open. We had to do our work, and if we were interested in sports or music, for instance, we were actually

given time. They gave us a room to practice in. There were very few schools in Ireland like that. Most were

Christian Brothers schools where you studied, did your work, and that was it.

We started the band as punk rock was bursting on the scene, and when we heard it, we said, "Wow, this is amazing. This

is energy!" Music was getting so boring. There seemed to be so much conveyer-belt rock where they'd just take

the money and run, but punk rock had raw power. A lot of the bands couldn't play, but they had something to say.

They gave us inspiration.

CF: Did you ever think that the isolation, and maybe even the adversity, you experienced in your formative years

in Ireland was an advantage? CF: Did you ever think that the isolation, and maybe even the adversity, you experienced in your formative years

in Ireland was an advantage?

LM: Yes. I don't honestly think a band like U2 could have come from anywhere else. We had time to grow

at our own pace, protected and away from the circus of the rock 'n' roll culture. We never got involved in that.

We live in Ireland; we record there. It's home; it's freedom. We can be ourselves, be with our families, and do

all the things human beings are meant to do. Our music comes from being around real people in the real world.

The title The Unforgettable Fire comes from a book we saw of paintings that were done by survivors of Hiroshima.

And if you listen very closely to Bono's lyrics in "Bad" from that album, he touches on the huge heroin problem, especially

in Dublin, and everything that surrounds it. We're very aware of those things. But go to London, and what some

people are influenced by is the fantasy "scene" – the clothes, the dancing girls, how many drugs you can take. We

just leave that behind. That's not what this band is about. LM: Yes. I don't honestly think a band like U2 could have come from anywhere else. We had time to grow

at our own pace, protected and away from the circus of the rock 'n' roll culture. We never got involved in that.

We live in Ireland; we record there. It's home; it's freedom. We can be ourselves, be with our families, and do

all the things human beings are meant to do. Our music comes from being around real people in the real world.

The title The Unforgettable Fire comes from a book we saw of paintings that were done by survivors of Hiroshima.

And if you listen very closely to Bono's lyrics in "Bad" from that album, he touches on the huge heroin problem, especially

in Dublin, and everything that surrounds it. We're very aware of those things. But go to London, and what some

people are influenced by is the fantasy "scene" – the clothes, the dancing girls, how many drugs you can take. We

just leave that behind. That's not what this band is about.

CF: You talk to the public about clean living and spirituality, but you manage to walk a thin line: You're

not wimps. You're still legitimate rock 'n' rollers. CF: You talk to the public about clean living and spirituality, but you manage to walk a thin line: You're

not wimps. You're still legitimate rock 'n' rollers.

LM: All the sex and drugs in rock is so old, so boring, and so pretentious. I suppose some people think you

have to go along with that old image to be a legitimate rock 'n' roller, but why should we pretend? If you actually

met a lot of big name rock 'n' roll bands as human beings, you find they're a lot straighter than you think. It's a

big game, and we don't play it. People can make up their own minds about U2. People who see us live know it's

not "wimp rock". LM: All the sex and drugs in rock is so old, so boring, and so pretentious. I suppose some people think you

have to go along with that old image to be a legitimate rock 'n' roller, but why should we pretend? If you actually

met a lot of big name rock 'n' roll bands as human beings, you find they're a lot straighter than you think. It's a

big game, and we don't play it. People can make up their own minds about U2. People who see us live know it's

not "wimp rock".

CF: CF: How would you describe your drum style, Larry?

LM: Well, I never thought of it as a style until somebody said, "You know, you have a really unique style." And

I said, "Oh really, what's a unique style?" It's hard for me to articulate what I do. Other people have to tell

me what they think. Once, there were two professional session drummers on Irish TV who took the drumbeats from "Pride",

and explained what they were in great musical terms, and explained how this technique was used. (chuckles) I mean, they

could be right, but I never thought of it like that! I just do what I do. I've developed into something myself.

Sometimes people ring me up, or write and say, "We think you're fab. Can you give us hints on how to drum?" The

only thing I can think of is something I learned myself and that is, "Hit 'em hard!" Just put everything into it; don't

hold anything back. LM: Well, I never thought of it as a style until somebody said, "You know, you have a really unique style." And

I said, "Oh really, what's a unique style?" It's hard for me to articulate what I do. Other people have to tell

me what they think. Once, there were two professional session drummers on Irish TV who took the drumbeats from "Pride",

and explained what they were in great musical terms, and explained how this technique was used. (chuckles) I mean, they

could be right, but I never thought of it like that! I just do what I do. I've developed into something myself.

Sometimes people ring me up, or write and say, "We think you're fab. Can you give us hints on how to drum?" The

only thing I can think of is something I learned myself and that is, "Hit 'em hard!" Just put everything into it; don't

hold anything back.

CF: But you know when to hit 'em soft too. You're capable of subtlety in your drumming. CF: But you know when to hit 'em soft too. You're capable of subtlety in your drumming.

LM: Yes, we like to put light and shade into the music as well – not always hammering away. There are

times to be lighter, but it's still strong. There are times to come down and go back up again. I don't hit the

drums at the same intensity all the time. LM: Yes, we like to put light and shade into the music as well – not always hammering away. There are

times to be lighter, but it's still strong. There are times to come down and go back up again. I don't hit the

drums at the same intensity all the time.

CF: Of course, one of the standard critiques of rock drummers is that they know nothing about dynamics. CF: Of course, one of the standard critiques of rock drummers is that they know nothing about dynamics.

LM: It may be true of a lot of drummers, but certainly not of all of them. You can't generalise, especially

now. There are so many new drummers with new ideas. It could be said, though, that in the past I was sometimes

just heavy-handed, but I think that, over the last few years, I've started to listen to music a lot more in terms of light

and shade. It's a question of maturity – of actually listening to more music and seeing other drummers. I

was never interested in other drummers until about two or three years ago. LM: It may be true of a lot of drummers, but certainly not of all of them. You can't generalise, especially

now. There are so many new drummers with new ideas. It could be said, though, that in the past I was sometimes

just heavy-handed, but I think that, over the last few years, I've started to listen to music a lot more in terms of light

and shade. It's a question of maturity – of actually listening to more music and seeing other drummers. I

was never interested in other drummers until about two or three years ago.

CF: "Drowning Man", on War, comes to mind as an example of light and shade. The bass drum resonates as if

from the depths of the ocean, with a stirring sense of ebb and flow. CF: "Drowning Man", on War, comes to mind as an example of light and shade. The bass drum resonates as if

from the depths of the ocean, with a stirring sense of ebb and flow.

LM: That song just evolved spontaneously. I did it with a 24" marching-band bass drum that I put up on a chair,

and just hit with a mallet and with my hands. It was recorded in Windmill Lane, the studio in Dublin that we use. It's

an amazing place, with its own character. You can get immaculate drum sound in the hallway, which is solid stone walls

with a really high ceiling. I set my kit out there, and they put mic's all the way down from the very, very top of the

stairwell. I've recorded many songs out there. LM: That song just evolved spontaneously. I did it with a 24" marching-band bass drum that I put up on a chair,

and just hit with a mallet and with my hands. It was recorded in Windmill Lane, the studio in Dublin that we use. It's

an amazing place, with its own character. You can get immaculate drum sound in the hallway, which is solid stone walls

with a really high ceiling. I set my kit out there, and they put mic's all the way down from the very, very top of the

stairwell. I've recorded many songs out there.

CF: You also use brushes on "Drowning Man". CF: You also use brushes on "Drowning Man".

LM: Yes, and on "Bad", too, among others. A while back, I started to use brushes on different songs, and it

seemed then that it was catching on. Are you familiar with the band Echo & The Bunnymen? They did a

complete album with just brushes; I really like it. The only thing is that so many drummers are using brushes now that

I've sort of stayed away from it slightly. LM: Yes, and on "Bad", too, among others. A while back, I started to use brushes on different songs, and it

seemed then that it was catching on. Are you familiar with the band Echo & The Bunnymen? They did a

complete album with just brushes; I really like it. The only thing is that so many drummers are using brushes now that

I've sort of stayed away from it slightly.

CF: There seems to be an Oriental streak in your playing, which I noticed first on "Drowning Man". CF: There seems to be an Oriental streak in your playing, which I noticed first on "Drowning Man".

LM: Oh, did you get Oriental flavours in that? In The Unforgettable Fire, there are many Oriental touches,

even in the design of the album cover, with the rich purply colour and the calligraphy. When we went to Japan, we avoided

all the "touristy" trappings. Most bands stay in rock 'n' roll hotels there; we stayed in traditional Japanese hotels

and ate a traditional Japanese restaurants. Everywhere we went, we heard the traditional music, and it was fantastic.

Obviously, we were all influenced by it. LM: Oh, did you get Oriental flavours in that? In The Unforgettable Fire, there are many Oriental touches,

even in the design of the album cover, with the rich purply colour and the calligraphy. When we went to Japan, we avoided

all the "touristy" trappings. Most bands stay in rock 'n' roll hotels there; we stayed in traditional Japanese hotels

and ate a traditional Japanese restaurants. Everywhere we went, we heard the traditional music, and it was fantastic.

Obviously, we were all influenced by it.

CF: You must also be aware of the marching-band influence, evident especially on War. CF: You must also be aware of the marching-band influence, evident especially on War.

LM: Oh, yeah, I see it, although it's not something I cultivated. It was just there. It was very, very

natural. Again, it was a case of someone asking me if I were ever in a marching band, because they could hear it in

my style, and I said, "Oh really, can you?" I didn't realise it, because it wasn't a conscious decision on my part. LM: Oh, yeah, I see it, although it's not something I cultivated. It was just there. It was very, very

natural. Again, it was a case of someone asking me if I were ever in a marching band, because they could hear it in

my style, and I said, "Oh really, can you?" I didn't realise it, because it wasn't a conscious decision on my part.

CF: The sense of open space is prominent in your drumming. There are times when you allow the absolute maximum

space between beats; you hold it to the last fraction of a second. CF: The sense of open space is prominent in your drumming. There are times when you allow the absolute maximum

space between beats; you hold it to the last fraction of a second.

LM: Yes, I like gaps; I like to be able to feel the music – not to clutter the songs. Lots of

new drummers tend to fill in all the gaps and not leave space. Technically, a lot of drummers leave me standing miles

away, but they don't leave gaps. It may sound good for their bands, but it's just not me. I've really been getting

into R&B drummers. They're right down to earth – simple. All those jazz-head drummers are just so complex.

It's like going to college. It's like "How intelligent are you? How many big words do you know?" It doesn't

really matter, ultimately. LM: Yes, I like gaps; I like to be able to feel the music – not to clutter the songs. Lots of

new drummers tend to fill in all the gaps and not leave space. Technically, a lot of drummers leave me standing miles

away, but they don't leave gaps. It may sound good for their bands, but it's just not me. I've really been getting

into R&B drummers. They're right down to earth – simple. All those jazz-head drummers are just so complex.

It's like going to college. It's like "How intelligent are you? How many big words do you know?" It doesn't

really matter, ultimately.

CF: There are some who would say that the technique – all those big words, if you will – gives you a

greater vocabulary to convey the musical message. CF: There are some who would say that the technique – all those big words, if you will – gives you a

greater vocabulary to convey the musical message.

LM: Well, to me it's like the difference between a novel and a poem. Sometimes, you can say everything in

one line or even one word. I don't mean to knock anybody; there's room for everyone. But what happened to the

whole punk thing – just getting up there and doing what you feel? I'm into the spirit, not into the musicianship.

I'm a big fan of Sandy Nelson. I remember trying to play with "Let There Be Drums" as a kid and thinking, "This is great!

I can actually do what this guy is doing." It had such a youthful spirit – such a great feel. And there

were mistakes on the record, which I really liked because I thought, "This drummer makes mistakes as well!" LM: Well, to me it's like the difference between a novel and a poem. Sometimes, you can say everything in

one line or even one word. I don't mean to knock anybody; there's room for everyone. But what happened to the

whole punk thing – just getting up there and doing what you feel? I'm into the spirit, not into the musicianship.

I'm a big fan of Sandy Nelson. I remember trying to play with "Let There Be Drums" as a kid and thinking, "This is great!

I can actually do what this guy is doing." It had such a youthful spirit – such a great feel. And there

were mistakes on the record, which I really liked because I thought, "This drummer makes mistakes as well!"

|